In this new episode of the Animated Documentary podcast, Carla MacKinnon talks to artist, animator and filmmaker Tess Martin about her recent animated documentary projects How Now, House? (2025) and 1976: Search For Life (2023), her creative exploration of forms and materials, her love of Clio Barnard’s The Arbour (2010), and the impact of new technologies on animated documentary production and commissioning.

Tess Martin is a film and visual artist based in Rotterdam, with a background in classical fine art and animation. Her work bridges screen-based animated films and site-specific installations and has been exhibited at leading festivals and galleries, picking up numerous awards. Work can be seen on her website and on Instagram. How Now, House? will be screening at Sheffield DocFest on June 21st and 22nd.

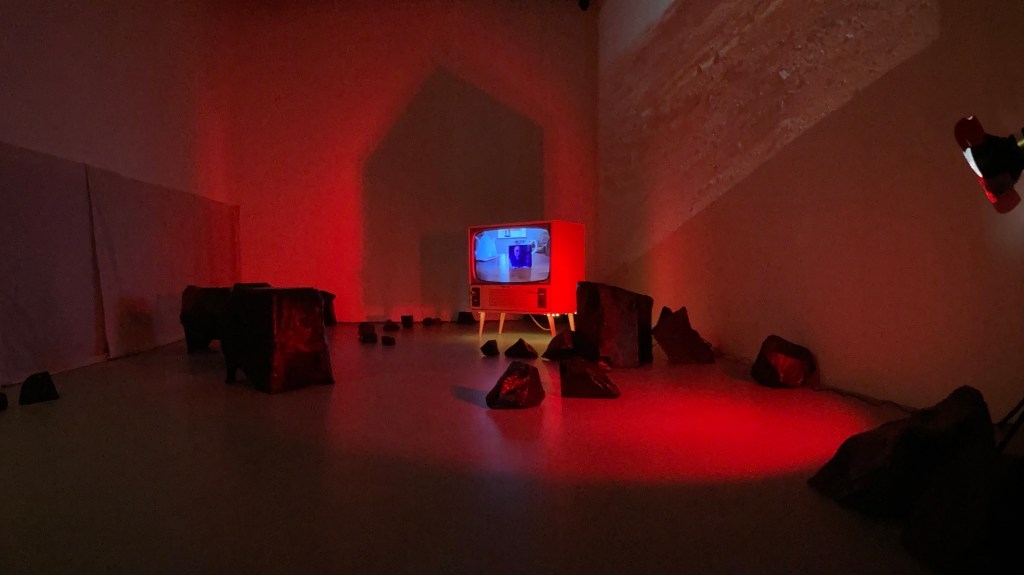

L-R: installation How Now, House?; installation 1976: Search for Life; film still 1976: Search for Life

Episode transcript:

CM: Could you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your practice?

TM: Sure. I am an artist filmmaker based in Rotterdam in the Netherlands. I’ve been here since 2014. I have a fine art background, I did a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Brighton, which is where I started making experimental animation. And then I did more recently a master of animation at a Dutch art academy called Saint Joost. And I have been making short films, but also installations, and I often do multiple versions of the projects and they develop concurrently. So I may actually first work on an installation version with the knowledge of the short film version in my head and then the short film version and then maybe come back to the installation. It all depends on opportunities for exhibition and funding. So it’s all it’s all a bit a bit of a mixture right now.

CM: Could you talk about how, once you have decided what you’re making, what the form of it is, how you would approach those different forms differently?

TM: I think I think it’s quite straightforward. For example, for this film that I finished a few years ago called 1976: Search For Life, I first started developing the installation version, and that that was only because I was interested in somehow displaying all of the research I had been doing. So I had physical objects. I had these vintage magazines from the 70s that related to the NASA Viking mission. And I had, um, some physical objects from this trip that my family took. And I had a video I had made that was kind of imitating an old school like slideshow movie that you would look at with relatives, like, I kind of kachunk slideshow. So I was trying to figure out how to bring all of this together. And the first natural way of doing that was, like, physically in a room with a soundtrack on headphones, which is something that I have started doing often. So even though it’s an installation, there’s still a very clear time based component because the, the viewer is walking around with these headphones on. Oh yeah, I also had this, like, model of Mars I had made that was rotating. So it was almost like a brainstorming way of figuring out how do they connect? What are people responding to? How do people behave in the space, and what does that say about the work and how they are interpreting what they’re also listening to at the same time? And then I use that opportunity to interview the people on their way out. So this is kind of part of the research phase. And then I can see what stuck with people, what really didn’t stick with people, what was missed, what resonated. And then I started doing more film experiments. So I started playing around with photographs in different ways. And and I started to really focus on frame by frame visual experiments, which kind of replaced that first film that I mentioned, the kind of slideshow film and that became the main film. And then I rethought the installation and realized that a lot of the ideas I had, I was brainstorming with at the beginning, I had incorporated into the film, so I didn’t need, for example, the magazines and the the tiny model of Mars and all these objects. And instead I made an installation with the video as like the focal point, but with a special television cabinet within which the monitor is placed and a special set that is kind of a fake Mars set that people walk into when they are watching the video. So I guess that’s what I mean by like they happen concurrently and and they influence each other so that the installation and the film are both quite different by the end. I hope that answers your question.

CM: Absolutely it does. And it kind of leads to another question I had, which is to do with the materials that you use. If looking back over your body of work, there’s such a range of materials from analog 2D running through computers and 3D spaces. How has that evolved in your work and what’s that relationship for you between the materiality of what you’re using, and the themes or the stories that you’re telling?

TM: Yeah, I mean, it goes back right to the beginning. You know, when I first started playing around with paper cutout animation, and the reason I even got into it at all was because of this puppetry show that I saw at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival between my first and second year on my Bachelor, and it was quite a well-known British puppetry troupe. And they they perform with the puppets on the stage without the puppeteers being hidden. And they’re often performing with the puppet that they are also manipulating. And I was so blown away by this idea of – the method is on display. The artifice is evident and yet we are still engaged. And in fact it just makes it more interesting. So this idea is what I took back with me, and that relates to the materiality and why I started, I think, using paper. And then for a long time I was using handmade papers, like papers with textures that were backlit, that were very clearly paper, there was no, you know, trying to make a photorealistic, you know, puppet of a human or anything. It was very accessible, cheap material that I could get stuck into very quickly. And for a while I was using these, these papers, and I think I was attracted to the paper because it was very delicate and it was easy to make it look really different depending on the lighting and depending on the layering, so I was. I liked this idea that the material might look like something when you’re looking at it with your eyes, but then in the film it’s quite different because it’s like arranged in a specific way. And so it kind of made it more performative. The ultimate answer is, I think I get bored quite quickly, so I need to stay engaged. And I enjoy experimenting with different techniques and what they can do that a different technique can’t. So each project is kind of different and sometimes it changes like sometimes I start with with one thing and then I’m like, actually, I think it needs to be this or it doesn’t need to be, you know, paint on glass, it’s not required. And actually, you know, something else might be more appropriate. So I try to stay open and I try not to start from like, I want to use this technique. I try to let it be led by the concept first.

CM: It’s interesting you mentioned the kind of the artifice of the animation and the image, because that’s something that scholars have talked about in relation to ideas of authenticity and the actual credibility of animated documentary as a form of documentary in documentary. So much of the storytelling decisions are hidden, and increasingly with the kind of post-truth new media ability to construct any kind of an image or any kind of a story that actually, by being transparent with the artifice, you are critically engaging an audience in the fact that what they’re watching isn’t a direct recording of reality, it’s an interpretation of reality.

TM: Well, yeah, I mean, I that resonates with me for sure. That is something that these, that these techniques do. Is it makes it very clear that this is a manipulated thing. And the interesting thing is when that still leads to truth in a sense. It’s much more interesting to me to have this supposed gap that is being bridged than to just have like a “real live action filming”, which can also be very interesting. And, you know, I completely appreciate that also on a different level. But then I’m focused on like the editing or like, are these people actors or are they subjects that are being interviewed? And some filmmakers play with that very nicely, one of my favorite documentaries of all time is called The Arbor from 2010. And I just love it. I watch it like once every few years because I just find it so inspiring. And I mean, that’s, you know, a live action documentary, experimental documentary. But I just love the way she plays with artifice and the fact that she’s hiring actors to play the characters. So there’s a lot of, like, doubling and layering And the real people are interviewed, but it’s actors who are lip syncing the words. And these types of things, which I think are a great way of using the medium. So they’re really taking advantage of the medium. Like – what can film do?

CM: And when you are working with real things, or working with that idea of some kind of truth telling, do you have a sense of how you navigate that truth? Finding your story and finding your truth in that that big amorphous thing of reality?

TM: In a way, I’m quite lucky that I’m not trying to tell some, like, objective truth story, you know? Most of my work comes from a personal place and is, you know, my interpretation of a situation or of events. And of course I love research and I love all of that. And I am very conscious of how the work purports to represent things in the world, but I don’t claim to be making the end all and be all truth about a certain subject. Nor would I want people to think that I was. I try to to first do a ton of research, to really feel like I’ve gotten a handle on it and like all aspects of it, as much as I think is necessary, and then try to focus on what is my relationship to this topic and how how do my thoughts interpret this idea. And that is truthful. It’s just it’s it’s just my version of it, which I hope, of course, that that is relatable and accessible, but it is always going to be my point of view. For example, this film I just finished about the house that I lived in for a long time. It covers many themes. It’s a 13 minute short. On the one hand, it talks about like literally the history of the house and like the people who lived there and these kind of factual things. And then it also kind of talks more philosophically about theories about time, which of course are there are a few different theories about time and how time works. That’s also not absolute. I was using the work of one particular theoretical physicist called Carlo Rovelli, who whose books I really found accessible. You know, I am not a theoretical physicist. There might be theoretical physicists who watch this film who might be like, aha! But that is just one of the theories. And actually and it’s like, cool, that’s totally cool. That’s I’m using this as a way to talk about something. And I’m not saying that this is, you know, how time works. So similarly for that film, there was a lot of factual information about the previous residents of this house. And also I interviewed my housemates, but at a certain point I chose to hire actors to read the lines that I wrote for them. So I wrote dialogue for the historical residence based on the real facts, you know? So, like, the names are real for the most part, except for a few that I that I thought sounded better. And then there was also kind of a practical reason for this, because of the privacy laws in the Netherlands, I don’t actually know who lived in the house after like 1965 until like 2012 when we moved in. So I also wanted to fill that gap. So I kind of made up a couple residents, who lived there in the 80s and 90s that were kind of based on educated guesses about what we found in the house when we moved in. And I hired actors to reinterpret some of the lines that my housemates had said in our interviews, because I wanted it to be a bit distant, like I just felt it needed to be… a bit fictionalized, really. And for the film, I think it was appropriate because in this way we get to hear from all of the residents equally, even the ones that that I wouldn’t have been able to interview because they’re no longer with us. So it kind of plays with this idea of time and like, wait, who are these people? And are they real and are they not? And are we listening to them now or, you know, when are we? Um, but I but it was important to me that everything they said was based in fact, because that’s already very interesting, like the the existing history of this house and these people is in and of itself already very fascinating and interesting. And that’s kind of what the film is about, was like this rich tapestry of people’s lives. I don’t need to make that up because that’s already the reality is already interesting enough.

CM: So you’ve talked a little bit about time as being a really strong theme in How Now, House? It also runs strongly through 1976: Search For Life and and some of your other work. Is that something that has developed over the course of your work, or was that something you were really interested in from the beginning?

TM: No, I think it’s a relatively recent theme that I’ve been stuck into for a while now. I think it all started when I started to get into family history research. So it was something that started from a non non-artistic practice place, and then it bled into my practice, and I started really being concerned with history and the past and our relationship to it, and how impossible it is really to truly know what happened or what someone else’s experience was. But we are still trying, we still want to. So this this urge that we have, I think is very interesting and worth highlighting despite its limitations. So the 1976 project started when I found this travel journal that was written by my father during this trip that him and my mother and my eldest sister, who was a baby, took. And so I was fascinated with this moment in my father’s life, when he was really at the beginning of his life as a father. He was going back to Scotland with his mother to try to investigate his roots. So he was kind of at this cross point in his life, which is a very different type of life than my life. And I’m in fact older now than he was at the time of this journal. He he also, coincidentally, happened to be writing about the NASA mission to Mars that was happening that same summer. And this idea that he was already accessing this dialogue between these two things, that he was on a trip and humanity was on its own trip at the same time, and how interesting that was to him. So I was going on also on a trip. So there’s three trips happening in this film. So that that was kind of the start of that project. And then I started to think of different ways to “go on this trip” towards this moment in the past, in my father’s life and feeling like you are getting as close as possible or or maybe have stepped into kind of a wormhole time situation where where everything is colliding and everything is happening at once, and each trip ends in a kind of bittersweet way. So kind of dealing with that also, and yet moving forward, that’s where that came from. And then at the same time, I was developing a different project, a very, very short film where the theme of time also came into it and also used this photo replacement technique in a different way, kind of more art history related, which was kind of related to letters I had found written by my mother to her mother. And this idea of photo replacement changed for How Now, House? Because in the the first two films, 1976: Search for Life and Still Life with Woman, Tea and Letter it’s literally a photo replacement of an image sequence, right? That comes from a video or originally a millimeter archival footage. So I’m like literally replacing the next image in the sequence, which, you know, animators will understand what that means. But for the house film, I started to realize that I could use a deck of playing cards in the same manner. So this theme of playing cards became kind of a metaphor in that film. And then I could shuffle the frames of the film itself, just like you would shuffle a deck of cards. And how this spoke to the interchangeability of time. And that’s what that project was trying to focus on, was like multiple people’s timelines together in one house. Anything sequential is you could you could make this argument for us somehow playing around with that sequentiality of whatever it is, which is kind of taking animation to its most basic definition. Right? Which I think is actually time. So the theme of time is inherent in any especially frame by frame animation, because what we are doing is we are manipulating time when we are making the film. So in that sense, I guess I’ve always had a theme of time, but this time it’s it’s more literal.

CM: I wanted to talk a bit more broadly about animated documentary or the animated nonfiction space. You’ve been working with animated nonfiction now for well over ten years. How have you seen that landscape evolve in terms of either the films that are being made, audiences or commissioning?

TM: In terms of commissioned stuff it used to be that most of my commissioned work was for other people’s documentaries. So other people are making a documentary, and then they want some animation, they want like five minutes of animation in it, and I haven’t done it in a while, mostly because it’s just too expensive for people. And to be honest, now with with AI, I’m not sure how long this will keep going. You know what I mean? Because a lot of these scrappy productions have other options now to to fill the gap that animation had been filling. So who knows what’ll happen there. And in terms of animated shorts that are that are documentary based, I don’t know, to be honest. I mean, I still see some, some delightful independent short films, at festivals and stuff, but I can’t say that I’ve seen a film like The Arbor recently, that that has completely changed my life or like, redefined to me what documentary could be, or what animated documentary could be.

CM: I think there’s often a bit of a gap between what animated documentary could be and what it so often is. A lot of my PhD work was around that, and it was looking at the kind of contexts that the work is made in, the production contexts, distribution, exhibition contexts that animation lives in industrially. And also that documentary lives in industrially. And how it’s very difficult to marry those within the markets in a way that is well supported. Additionally, and probably because of that, there’s maybe some skills gaps in production. But I think that because of that, it can be very difficult for very ambitious work and particularly long form work to get made and to meet its ambition, which I think is why we see such exciting work in a short form space, very rarely scaling up.

TM: Yeah. That’s true. Yeah. I mean, here in the Netherlands, sometimes there’s a couple of funding schemes that fund interesting work from artistic makers. There was a fund that was a collaboration between the Mondrian Fund, which is the Arts fund, and the Dutch Film Fund, and it was to fund first feature films by artists. And there was a couple kind of interesting films made through this scheme that would not have otherwise ever been made. One of them was by Fiona Tan, and it was it was using archival footage of the Netherlands from the 1920s, juxtaposed with letters written to her by her father in the ’70s. So it was it was also kind of dealing with time and the past and the incongruity of these two things, which was, yeah, interesting. It was interesting. I don’t know if it really needed to be that long for what it was, but I appreciated it. And you get a lot of funds that are trying to push new technology and new technological developments. So I do sometimes see some kind of creative and interesting VR projects that I’m curious about or even like video game projects, which are cool. You know, it’s it’s not my medium, not right now anyway. But I think that’s great to encourage this new stuff because it’s very interesting and inspiring how some people are using these technologies. But it is always kind of funny to me that the funds are like ultimately trying to fund technological research, like the arts funds are trying to push their country’s edge in the technology fields, which is like, okay, there’s, you know, as someone who does frame by frame animation with basic materials, sometimes it’s like, okay, but just because it’s new doesn’t mean it’s… what about what about the existing techniques.

CM: Can you tell us what you are currently working on?

TM: I’m working currently on a longish short film that is that is not documentary in any way. It’s kind of a science fiction story. Having said that, there’s a lot of real research gone into it because it’s kind of a multiverse story. So there’s a couple different like settings and different timelines, but it’s about an otherworldly creature who is traveling around observing humans and starts to relate to them. It’s like a photo cutout technique. So as opposed to photo replacement, which we were talking about, it’s like literally actor footage that has been cut out. The video is turned into an image sequence at a specific frame rate, and then these are printed and cut out and then animated on the multi-plane. So it’s it’s kind of a weird flat perspective. So that’s that’s what I’m doing now. I’ll be working on it for a while, but I’m also developing the installation version of How Now, House? that I’m going to be displaying in a little tiny space here in Rotterdam that’s in and of itself, a little old bridge watcher kiosk. And then I’m starting to maybe visit some festivals with How Now, House?. The European premiere will be in Sheffield, actually, in an about a month and just trying to plug away, plug away every day.

CM: And where can people find your work?

TM: There’s a lot of stuff on my website and I have a newsletter that I send out maybe every six weeks with updates and stuff.

CM: Thank you so much. It’s been absolutely brilliant talking to you.

TM: You’re welcome. Thank you.