In the new episode of the Animated Documentary Podcast we talk to director Rosie Schellenberg. Rosie has over twenty years of experience making award-winning films and television programmes. Her latest film, Turner: the Secret Sketchbooks, broadcasts on Wednesday 19th November at 21:00 on BBC Two. This stunning biographic documentary, looking at the life of the pioneering painter J.M.W. Turner, includes numerous animated sequences created by animation duo Tjoff Koong (Tezo Kyungdon Lee and Magnus Lenneskog) at Passion Pictures. These animations both reconstruct Turner’s historical environment and evoke his inner experience. The animation in this documentary is sensitive, imaginative and powerful, and is essential to the film’s creative essence.

We spoke to Rosie about the process of making the film, and what animation can bring to documentary storytelling. Listen to the interview here or read the transcript below.

(Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks, Passion Pictures, BBC Arena, Tjoff Koong Studios, © 2025)

CM: Can you give a short introduction about yourself and any highlights of your career that you’d like to mention?

RS: I’ve been making documentaries for a number of years. I started out at the BBC as a director, where I had some amazing opportunities to work on series like The Culture Show and on BBC Four, arts projects and history projects. So that was where I cut my teeth in directing. And then I went on to make films for BBC One and BBC Two before becoming freelance and working on formats like Who Do You Think You Are? and Long Lost Family. And it was actually developing a new strand of Long Lost Family called Born Without Trace that I won a BAFTA and an international Rose d’Or – that was about reuniting foundlings, people who’d been left as babies, and using DNA for the first time on television to reunite them with their birth families. And that was a bit of a departure for me, because I’d been doing a lot more of history and arts projects. But it’s through doing that kind of emotional storytelling that’s led me on to do a series of biopics and the most recent one on J.M.W. Turner, the painter, has involved using animation to tell his story. Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks is rooted in these incredible thirty-seven thousand drawings that Turner produced during his life, and they form the spine of the film and offer jumping off points into his psychology. My storytelling is rooted in trying to understand psychology and emotion. Animation opened up a whole world, a sort of imaginative world where we could think about Turner’s life in not only an emotive way, but in an immersive way, in the period and in the style of his work. So it was fusing lots of different elements to communicate the experience of Turner’s life.

CM: And was that something that you knew you wanted to use from the beginning of the project, or at what stage did you start to think, ‘okay, animation is a good way to do this’?

RS: I was brought on to direct the project, and that decision had already been made because Passion Pictures, the production company behind the film, have a strong animation background. Offering this animated element was a big part in winning the commission because it felt contemporary, distinctive, and rooted in Turner’s own world, rather than using dramatic reconstruction. This felt like an imaginative layer that was appropriate to Turner himself.

CM: Had you worked with animation in any of your previous work?

RS: I’d used small amounts of animation, mainly for maps or visual clarification, but nothing on this scale. But I had just finished making a drama documentary series, so I was thinking a lot about how to illustrate a biographical story in a way that feels expressive rather than just literal. You know, not just saying or showing what’s being said, but thinking how the visuals can really elevate a story. And what I found in the drama doc series that I’ve been working on is that it was the more subtle, evocative shots that conveyed the story, and I really wanted to bring that through to Turner. I knew what the animation had to illustrate because it was taking the place of something like drama, but it could do a different job for us. It was in place right from the start and the decision about who the animators were going to be helped lead the narrative.

CM: Did Passion Pictures have particular animation directors or animators who they knew that they wanted to work on it at that point?

RS: Yes, they had put forward Magnus and Tezo as possible animators, though the final decision hadn’t been made. But when myself and the producer, Rosy, saw Magnus and Tezo’s work, we were really captivated by it because it’s a very bold, graphic style and very landscape orientated. So not character and spoken word, but evocative landscapes that felt very contemporary. The palette, the shapes, the movement and the choice of shots was very filmic, and what they tried to do is see everything like through a camera angle, whether that’s like a drone or a POV shot, or looking down on someone’s legs walking. You can imagine a camera being there, so it felt very cinematic. As well as being evocative and landscape based, from the outset I wanted it to be immersive. So in all the shots in the film for the whole hour, there is nothing modern. The interviewees sit against real backdrops in a Georgian location. The shots of places are ones where you can’t see any modern life, and we’ve taken out any telephone poles or satellite dishes. And then, of course, the animation is very much immersing us in that world of two hundred, two hundred and fifty years ago.

CM: In terms of creative decisions and aesthetics, how much of that came from the animation directors, and how much of it came from you as the overall director of the piece, or from other members of the crew?

RS: It was a real team effort. There were two execs on the project and two commissioners. One of them is a very experienced Arts Commissioner, Mark Bell, and he’s seen a lot of animation in various films, and he had some really wonderful steers. As did the exec producers. And I think the key thing that we had to decide was how similar to Turner’s sketchbooks the animation would be and how different. So how much was inspired and evocative of the sketchbooks, but how it moved things on so you wouldn’t get confused. I think it was a challenge that the very element that had got this over the commissioning line was the animation, but you’re dealing then with two 2D elements – animation and sketchbooks. And how are you going to differentiate between them? Getting that right was quite difficult. I’ll give you an example: in the style frames when they generated an element of Turner’s body, like his hand, it was in an outline, a sketched outline, that looked great on a style frame. But when it was animated, it just didn’t quite look real. The blocked out hand looked better, and we had to decide whether we would use these more sketched elements or more blocked forms to illustrate his world. And that just took a bit of time because people had different ideas about it, and it took a while to get it right and make it consistent through the film.

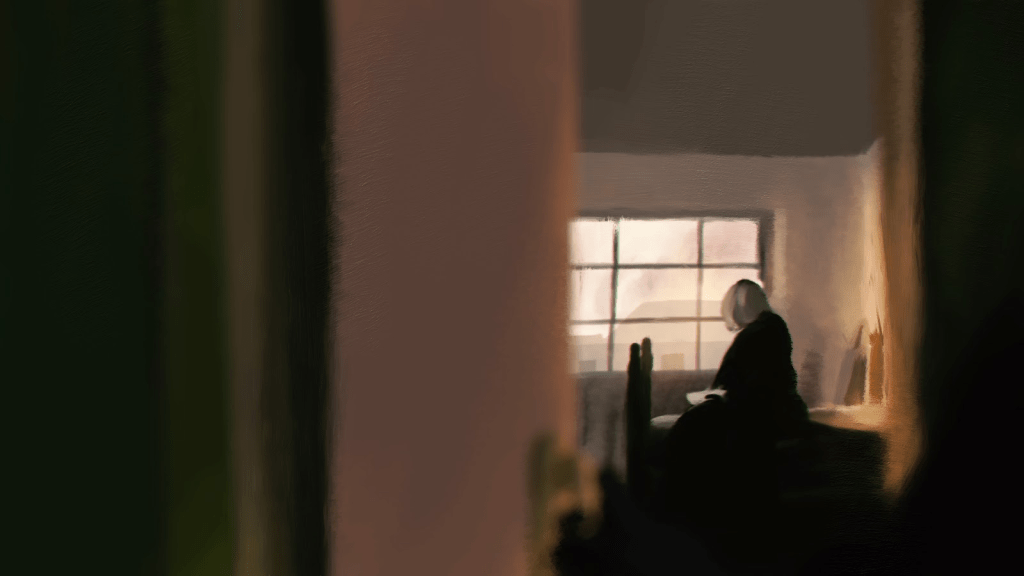

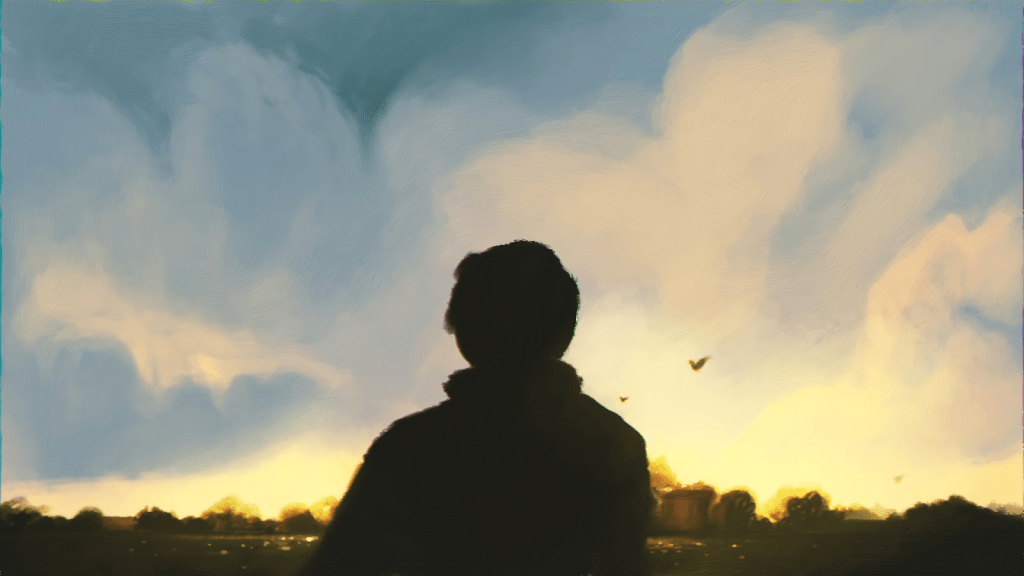

Magnus and Tezo’s style was really appropriate for the landscapes, and we got them on board early. And so knowing that they were going to be able to illustrate these landscape and travel sections so brilliantly steered me in the direction of doing the travel sections. So about twenty minutes into the film, Turner goes off to Switzerland and he goes on this wonderful carriage journey, and then he’s up in the mountains. So that was one of the first things I knew we would do, and that would look perfect in Magnus and Tezo’s style. But actually we’re delving into the psychology of Turner and his childhood, and that’s the foundation of his story. And so earlier in the film, we needed to illustrate interior scenes with people like his mother, who had mental health issues. So it was trying to use the style of the landscapes, but in an interior setting, so we did away with a lot of detail. We used planes of color inside on the walls, as if they were like a mountain to try and tie in those different elements. I think it works really well. The interiors have a sort of freshness about them, and a starkness which feels consistent with the rest of the film.

Above: Turner’s mother glimpsed through a doorway (L); Turner’s carriage journey to Margate (R) (Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks, Passion Pictures, BBC Arena, Tjoff Koong Studios, © 2025)

CM: You talked a bit about style frames, and obviously there’s preproduction methods that get used in animation which might be different from live action production. Was there anything that you found unfamiliar in that process or anything that surprised you or you found particularly useful?

RS: I think there is a clash of cultures when it comes to an edit with a documentary, and particularly one like this, because we had an incredible cast of quite well-known people. Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones; Chris Packham, the environmentalist; Orna Guralnik, the psychologist from Couples Therapy; Tracey Emin; John Akomfrah, the filmmaker; and artist Timothy Spall, the actor who knows everything about Turner’s biography, having played him in Mike Leigh’s film Mr. Turner. None of those people were going to read from any kind of script. They have their own views about Turner, and they all had a different angle to bring to the programme, although of course we steered them in the direction of the story we wanted to tell. And it is a complete biography, so you have certain beats that you need to hit. But they were still going to say their own thing. So when you get into the edit, there’s a lot of shaping to do. There were a lot of moving parts, but of course with animation you need to have it scripted. You need to know what you’re going to say. So balancing all of their incredible contributions and making it a coherent narrative just takes time. Whereas with the animation, we had a schedule – style frames, animatics, moving tests – and it was hard to hit all of those targets when so many elements of the narrative was shifting. Having said that, the beats remained the same, but we did move them around. And so the exact timings of things were impossible to gauge until the end of the offline. So it was quite hard to stick to the schedule in terms of the animatics in particular, and they fell off slightly; it was more style frames and then going straight to animation. So I think due to the parameters of blending documentary with animation, we had to cut our cloth and not go through all of the elements of the animation schedule that would have been possible in a in an ideal world. I think another big problem is that people in documentary don’t want to see black holes, you know, they want to know ‘what are we going to see here? How are the visuals going to really move the story along?’ And we’re like, ‘well, that’s going to be the animation part’. And I think it was hard for everybody to imagine what it was going to look like. And it really wasn’t until the post-production stage that that fell into place.

CM: Is there anything that you’ve learned through your production process that you think is worth sharing with others working in animated documentary?

RS: We were able to build a great relationship between the production team and our fabulous animators, and that was very much thanks to Rosy Rickett on the documentary side and Louise Simpson from Passion Animation. And having got our animation team on early, we were in a good place to get the animation elements into the film early, so in some ways we should have just felt really confident about that and got those style frames done as early as possible. Whereas that decision making did get pushed back. But having said that, I think the bravest thing to do is to commit to your animators, wait until the end of the offline, and then do the animation. And people just have to live with that part of the process. I think the problem with documentaries is you’re often up against a transmission deadline. And luckily we weren’t. So we had the ten weeks for the animation to take place after the end of the offline. There was a healthy buffer zone in the schedule to allow for that to happen.

CM: Your approach sounds great in the sense that you had your animators on at the beginning, so you can work with them at the end, but you’ve already been steered by what you know their styles and strengths are. Were you in dialogue with them in those early stages about what would be possible?

RS: Yes, we brought them in as early as possible, and they began doing the face development. For a while we were thinking we would show Turner’s face, and one of the big decisions was actually not to show his face and to be a bit more elliptical. So that was something that evolved during the course of the development stages. The animators were very much involved in the early discussions and we got them into the edit as soon as we could. It was Tezo who really began doing the style frames at the beginning, and we sparked up a fantastic relationship through those early conversations, I can only describe it as a kind of telepathy. I’ll give you an example. When we were still thinking about doing Turner’s face, I asked Tezo to create a style frame of young Turner at the age of about ten, and when he showed it to me, having never seen a picture of my son, I promise you it looked exactly like my ten-year-old. It was uncanny. And there were other times when I would be off doing some filming, you know, getting a GV, getting a shot of a church or buildings. And at the same time, Magnus and Tezo would be doing a style frame of what would have been Covent Garden at that time. And I hadn’t really thought that the transition shot would be something I was filming that day. But the style frame and the shots I was filming matched up, and so I was able to create these transitions retrospectively from the live action material, just because we were very much on the same page. So that obviously helped the process. We just were very much aligned and you can’t predict that. But when it happens, it makes the whole process so much easier.

(Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks, Passion Pictures, BBC Arena, Tjoff Koong Studios, © 2025)

CM: Can I ask you about sound? I think often the effectiveness of animation is so contingent on sound, and sometimes music. Again, to what extent were you marrying up those draft visuals or those style frames with the kind of music you might be using? At what point did that start to get put together to create the tone?

RS: The soundtrack for the film evolved through the course of the edit. We wanted something contemporary, but that was also orchestral and appropriate for the subject matter. The thing that really lifted the animation, which came after the animation had been created, was the sound effects – the wind, the sounds of steps, the birdsong, things like that did really help to evoke the world, especially because they were historic sound effects. I think they really help with the immersion in the world that the animation created. The other important thing was the transitions into the animated world. And we did put a lot of thought into how we did that, and we used sound to kind of give a sort of whoosh into this new world that we were creating. So subliminally, you knew you were going away from live action, and we chose shots and filmed shots that would blend with the animated world. I think the most successful one was actually suggested by our producer, Rosy, and that was to film a pipe, an old Georgian pipe in an ashtray with the smoke weaving up into the air. And that just went beautifully into an animation.

CM: Do you think you’ll be working with animation again?

RS: Definitely. And I’m thrilled to be in touch with you and to think about different ways that the animation community and whatever I will be working on could work together, and thinking in a more imaginative way about how animation can help with documentary and communicating different things. I think I’m going to go on to work on something that’s a bit more info heavy. But what kind of animation can help with that? Graphics? And how can different elements can be tied together? On the Turner program we did also have graphics, sometimes the sketches animate onto the page, and the historic stills have all been treated so they have a 3D effect. So there was also that element that keeps the visuals lively and interesting. It was great to be able to combine those different elements and see them as quite separate in some ways, but also how they can work together.

CM: You mentioned earlier that you studied at Central Saint Martins?

RS: I did a foundation course at Saint Martins, and I have kept sketchbooks and done art throughout my career. So I did really feel that working on this and being back in a very visual world, both because of the subject matter and the way we were illustrating it, really connected to a much more creative, painterly world that I was interested in getting into before I got into documentary. So it was a great way of marrying all those interests.

CM: It would be wonderful if there were more models for being able to combine those worlds, bring those worlds together, because I think so much of what we see in documentary is about trying to get inside people’s experience.

RS: Yeah. And there’s a very limited palette in a way. If you don’t go into animation, you’ve got archive and historic stills and things that you can shoot now. But there is this whole other realm, a 2D realm that can be so expressive. And what Magnus and Tezo achieved, as well as illustrating beats from Turner’s life, is an emotional layer; they somehow captured through the visuals a level of evocativeness that I think people forget visuals can do. So often in documentary you’ve got an illustrated essay, and this is going beyond that, going beyond the spoken word and creating something that really elevates the emotional experience. And I think that’s what animation was able to do in this case.

CM: Thank you so much, Rosie. We’ll be tracking your future work, which I hope will involve a lot of animation!

__

Turner: the Secret Sketchbooks will broadcast on Wednesday 19th November at 21:00 on BBC2.

You can find out more about Rosie Schellenberg’s work at: rosieschellenberg.co.uk